Happy New Year! In case you can’t make it to Times Square to watch the ball drop, here are a few unique ways to usher in 2022. Most of these practices come from the British Isles. (Excerpted from a Mental Floss article by Keith Johnson).

First Footing: Throw NYE party at you home, but to avoid bad luck, be sure not to allow a woman to be the first to cross your threshhold.

Take in, then take out: Don’t take anything out of the house without first bringing something in. “Take out, then take in/ Bad luck will begin. Take in, then take out/ Good luck comes about.”

Throw bread at the door: People baked a “barmbrack ”, an unusually large loaf of bread, on New Year’s Eve. The man of the house took three bites, then threw the loaf against the door, while those gathered prayed ”that cold, want or hunger might not enter” in the coming year. Hope they didn’t waste that bread.

Attend a “Watch Night” service: In the 1740’s, John Wesley (founder of Methodism) revived the ancient tradition of holding long, contemplative church services, to give coal miners something uplifting to do lieu of drinking the night away in a pub. By the 19th century, this had become a NYE tradition.

“Dipping” : Open a Bible to a random page and, without looking, point to a random passage. The excerpt selected was thought to predict the fortune of the dipper. This custom was widely used at other times to predict things.

Silly Resolutions: This custom sounds like a fun party game. Each player writes a silly resolution on a piece of paper and places it place in a bowl with all the others. Everyone draws a resolution and reads it aloud. Some suggestions from an 1896 games book include “I must stop smoking in my sleep” and ”I must walk with my right foot on my left side.”

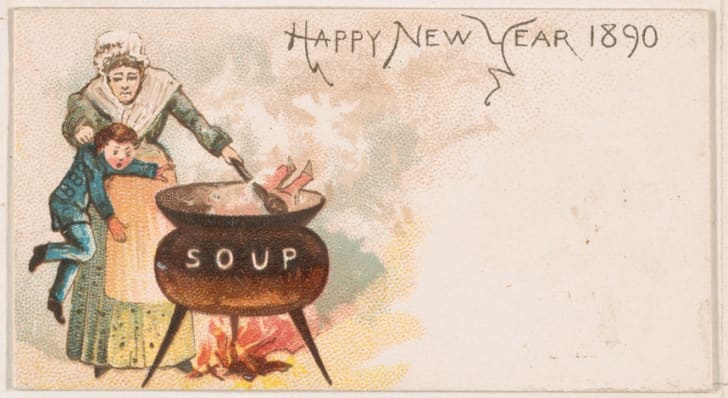

Send some New Year Cards:

In case you’re not tired of addressing all those Christmas cards. You’ve gotta wonder about this one, though……

Chunky and noisy,

Chunky and noisy,